Blog Archives

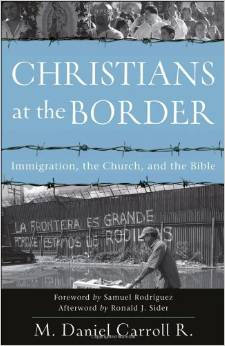

Book Review: Carroll, Daniel. “Christians at the Border: Immigration, the Church, and the Bible.” Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2008.

As is the case with Hoffmeier (the author of “The Immigration Crisis”), Daniel Carroll likewise meets the preliminary bipartite credibility test of any discusser of the topic of immigration: at one point he made abroad his abode for a sizable amount of time and has had close social intercourse with immigrants. As a minor he together with his family spent lots of summers immersed in the culture of Guatemala—the birthplace of his mother. Upon graduation from seminary this part Latino and his wife headed back to his “motherland” where he taught at El Seminario Teologico Centroamericano and did not return to Denver Seminary until fifteen years later. His interaction with Hispanics did not stop with his return to Denver. There he helped establish a Spanish-speaking training. He attends Hispanic services and has served on the board of the Alianza Ministerial Hispana.

As is the case with Hoffmeier (the author of “The Immigration Crisis”), Daniel Carroll likewise meets the preliminary bipartite credibility test of any discusser of the topic of immigration: at one point he made abroad his abode for a sizable amount of time and has had close social intercourse with immigrants. As a minor he together with his family spent lots of summers immersed in the culture of Guatemala—the birthplace of his mother. Upon graduation from seminary this part Latino and his wife headed back to his “motherland” where he taught at El Seminario Teologico Centroamericano and did not return to Denver Seminary until fifteen years later. His interaction with Hispanics did not stop with his return to Denver. There he helped establish a Spanish-speaking training. He attends Hispanic services and has served on the board of the Alianza Ministerial Hispana.

The target audience of the book are Christians from both the majority and minority culture. The goal of the book is to attempt to offer the divine viewpoint on immigration. The heart of the book is chapters two, three, and four, to which we now turn.

In chapter two, Carroll contends that folks from elsewhere who are abroad with the intent to stay and members of the host country alike are people first and then immigrants or citizens. People are made in the image of God, which means that both the immigrants and the citizens are bearers of God’s image. The implications of this observation in Carrol’s opinion are as follows:

(a) Immigrant have an essential value and possess the potential to contribute to society through their presence, work, and ideas. There would not be a David without Ruth the immigrant. Joseph ended up saving the whole of Egypt from famine

(b) Irrespective of whether they are here with or without the documents the government might mandate, to turn them away or to treat them badly is ultimately a violation against God. Egypt didn’t turn away the migrant patriarch and his family. On the contrary, she was charitable and willing to meet their needs.

(c) One way those of the majority culture can reflect the divine image is to demonstrate compassion for others the same way that God is portrayed as compassion not only toward His own people, but also to those beyond the community of faith.

(d) Immigrants should value the people of this country as those made in God’s image.

Chapter three opens with a brief exploration of the ethics of hospitality in ancient Israel. Hospitality extended to strangers by the likes of Abraham (Gen 18), Laban (Gen 24), Ruel (Exod 2), the concubine’s father (Judges 19), the Shunammite woman (2 Kings 4), the widow of Zarephath (1 Kings 17), Job (31:32) serve as a model to the majority culture in the manner in which it treats (Hispanic) Immigrants. It then surveys Old Testament laws concerning immigrants and other foreigners.

Part of chapter three analyzes the four terms (nokri, zar ger and toshav) used in the Old Testament to refer to outsiders. Accordant with Hoffmeier, Carroll concludes that nokri (including (nekhar and its feminine form) and zar refer to a foreigners in Israel who either have not been in the land very long (e.g., Ittai in 2 Sam 15:19; Ruth) or have not integrated themselves fully into Israelite life. The Law prohibits this kind of foreigner from becoming king (Deut 17:15) and from participating in some of Israel’s rituals (Exod 12:43; Ezek 44:7, 9; Lev 22:25). The third term, toshav, is akin to the previous two in the sense that it refers to foreigners who are similarly not assmiliated. (ger/toshav) To Carroll, the last term in the list of four ger, is not so much a designation of legal status (contra Hoffmeier) as it is an indication of itinerancy; thus his preference for the translation “sojourner.” The “sojourner” unlike the nokri, zar and toshav exhibited a high degree of assimiliation in the spheres of religion, language, law. It is Carroll’s opinion that just as the biblical imperative of caring for the sojourner is binding to the host culture, there exists a scriptural expectation that the sojourner learns the ways, language of the adopted country.

In chapter four, Carroll brings the New Testament to bear on the subject of immigration. While acknowledging that the Gospels are void of explicit teachings on immigration, Carroll argues for the existence of relevant passages. The story of Jesus’ flight to Egypt most certainly resonates with immigrants who have had to flee their homes for fear of their lives. Assuming that the “stranger” in Matt 25:35 refers to a disciple who goes to another land for ministry, the Son of Man and the Father will demand an accounting of the actions of Christians composing a host country towards Christian immigrants.

Moving on to the Epistle of 1 Peter Carroll hypothesizes that besides the accepted perspective that Christians are aliens and strangers in the world because of their faith, they were aliens and strangers in a concrete sense.

Carroll culminates his discussion of immigration vis-à-vis the New Testament with a look at Rom 13. In his opinion, if the Government laws, such as American Immigration Laws, are problematic theologically, humanely, and/or pragmatically, heeding those laws is tantamount to allowing oneself to be shaped by the “pattern of this world” (cf Rom 12:1).

IMMIGRANTS IN THE BIBLE: LESSONS FOR BELIEVERS PRESENTLY LIVING IN DIASPORA

Introduction

How much a reader identifies with a particular aspect of Scripture depends on the extent to which the reader has actually experienced that facet. The less the overlap between a text and the reader’s experience, the less the reader will identify with the verse. Conversely, the greater the overlap between the text and the reader’s experience, the more the identification.

This linkage or lack thereof between experience and identification ought not to be confounded with reader response hermeneutics. In the latter, the reader’s experience shapes his or her interpretation. In the former, the reader’s repertoire of experience, while it does not correlate with his or her ability to understand or interpret, either enhances or dilutes his or her appreciation.

In the same way that, for instance, the story of the betrayal of Jesus will resonate with one who has experienced betrayal or a woman who has experienced vaginal birth will identify with biblical references to birth pangs, I find myself riveted to stories of immigrants in the bible for the simple reason that I too am an immigrant. I invite my fellow aliens to join me in a discussion of immigrants in the Bible; circumstances surrounding their immigration and lessons and principles that they present us based on their experiences abroad. First in our list is an “Iraqi” (ancient Ur of the Chaldeans or Mesopotamia) triad whose ultimate destination even though they did not know until they arrived was a region that includes present-day Israel.

The Triad of Abraham, Sarah, and Lot

Circumstances Surrounding their Immigration

Not many of us would claim to have been recipients of a crystal clear divine address instructing us to proceed abroad and tying our obedience with promises of massive lineage, name recognition, and translation into a conduit of blessing as was the case with Abram (cf., Gen 12:1). Similarly very few of us, if any at all, boarded our means of transport without knowledge of what county we were heading to as was the case with Abram (see Heb 11:8).

Having said that there are some who, even though they may not claim to have heard the voice of God’s, will testify to the workings of God that transformed their immigration from a wish to reality. I remember making a deal with God that I would only travel if my wife also got a visa. I interpreted the visa issuance as the green light from heaven.

Speaking of spouse, there are those among us who dig Sarah in that like her they tied the knot with their sweethearts at home and then accompanied their spouses or there are those who feel Lot in the sense that like he they accompanied a relative abroad. A far bigger percentage of us are able to sympathize with the psychological struggle and emotional turmoil that the twosome would have gone through in their decision to move away from a surrounding that they had gotten used to and settled in for at least sixty years. Abraham was seventy-five years old when he left for Canaan (Gen 12:4). Sarah was ten years his junior (Gen 17:17). Even more torturous is the realization that Abraham’s daddy, Terah, passed away while Abraham was abroad (cf. Heb 11:32) and there is no evidence that the son experienced the closure like one would if he or she goes back for the funeral or sits over the grave and cries to tearlessness. How my heart goes out to Abraham. While overseas we lost our third born brother. Sometime later our last-born brother passed away. About a year ago my mum slipped into eternity.

Lessons and Principles

There is time to share space and time to amicably part ways

Whether the space is pastureland, as was the case with the triad of Abram, Sarai and Lot or a crib, as would be our case, how long the host continues to share space with a brand new arrival, who would most probably be a relative or an old acquaintance, depends on how soon the stay hits the tipping point. For the triad, the deal breaker was strife caused by too much livestock in too little pastureland (Gen 13:6-7). For us the tipping point may be any number of things—the guest’s unwillingness to share in domestic chores or, when able, failure by the person being hosted to contribute financially towards the day-to-day household expenditures, feelings of “suffocation” because the visitor is overstaying his or her welcome, growing signs of contempt bred by familiarity, etc.

The challenge posed to us by the triad is to part ways with the person we have been hosting without jarring the relationship. A sure way of ensuring that the relational ties remains intact is to foster the necessary conditions that will allow for soft-landing for the guest on his or her way out. Abraham soft-landed Lot when he allowed him to go first in choosing the land that he would settle in (Gen 13:9).

with the person we have been hosting without jarring the relationship. A sure way of ensuring that the relational ties remains intact is to foster the necessary conditions that will allow for soft-landing for the guest on his or her way out. Abraham soft-landed Lot when he allowed him to go first in choosing the land that he would settle in (Gen 13:9).

Twice I have hosted a relative and in both instances I did provide a soft-landing for the individuals on their way out. I did not part ways with the guests until they found another place to move into. I was willing to part with items such as utensils, sheets, and blankets that I knew my departing guests would need as they settled in their new location. Because I fostered the conditions for soft-landing my relationship with these two individuals has remained intact and healthy.

Deception for the sake of self-preservation spells JEOPARDY

If you haven’t lied of late, it may just be that your existence has not been threatened. The truth of the matter is that we are most tempted to lie when our own survival is at stake. The sole reason for Abram pulling wool over the eyes of Egyptians was self-preservation (Gen 12:12-13). Unfortunately, while the fraud may win you a new lease in life, it does place other aspects of your life in jeopardy. Abraham lived to see another day but he faced the possibility of living the rest of that life without his wife who were it not for God’s intervention would have become Pharaoh’s wife.

Think of all the lies that some of us have engaged in abroad when things dear to us as life itself have threatened to slip away from or elude us; such things as the opportunity to work or the chance to regain, maintain, or upgrade legal status. Now think of what we have placed at risk as a result of our lies. Misrepresenting your status to gain employment may earn you the money that you desperately yearn for but it does block employer-based path to permanent residency since you can’t have your cake and eat it too. As a believer divorcing your spouse in order to marry a citizen causes both you and the divorcée “to commit adultery.” (Matt. 5:32; Luke 16:18). Not to mention that if the ruse is uncovered you risk being fired, incarcerated, or even repatriated.

A Homeward Orientation inclines us to tune in to the news at home

Whether we tune in to or tune out the current affairs at home depends on whether we continue to possess or have lost a homeward orientation. In the person of Abraham, homeward orientation manifested itself in his strong desire, which he was careful to make known in his last will and testament, that his son Isaac only marry a woman from his homeland (Gen 24:1-4). Little wonder then that Abraham had his ear on the ground long enough to know the latest update on the family situation of his brother (Nahor) back at home (Gen 22:20-22). This update was crucial because as it turns out Bethuel, one of the several sons born to Nahor, became a father of a girl (Rebekah) who later on would become the wife of Isaac and in so doing fulfill the desire that Abraham had expressed in his will.

Bethuel, one of the several sons born to Nahor, became a father of a girl (Rebekah) who later on would become the wife of Isaac and in so doing fulfill the desire that Abraham had expressed in his will.

Homeward orientation for many of us exists for the simple reason that we still have loved ones back at home. Because of the presence of these loved ones at home we find ourselves continuously praying for the prosperity of our homelands since in the words of the prophet Jeremiah “in its welfare” our relatives will find their welfare (Jer. 29:7). Besides praying we call or text or facebook or google just to know what’s going down at home.

Declare your preferred burial location whether abroad or at home

All of us abroad will be buried either at home or in Diaspora. The question is whether we will have made our preference known prior to passing on. By not making our preference known before death we are delegating the decision-making process to someone else. Abraham seems to have made the decision for Sarah (Gen. 23:19) and by purchasing a burial ground he may have tipped his hand as to his preferred burial location, viz, abroad (Gen 23: 17-18).

and by purchasing a burial ground he may have tipped his hand as to his preferred burial location, viz, abroad (Gen 23: 17-18).

Joseph

Circumstances Surrounding his Immigration

Unlike his great grandfather Abraham who embarked on his trip abroad voluntarily, as a married and a much older man, Joseph arrived in Egypt single and barely eighteen. Did you arrive abroad single and young? Having arrived abroad single, did you then marry a native of your new residence (Gen 41:45), bore children with him or her (v. 50) and learned the language of your adopted home (42:23)? Then Joseph is your parallel. Did you show up abroad against your will? Then you are indeed Joseph-like seeing that according to Joseph’s own characterization and the narrator’s account, he was a victim of kidnap (Gen 40:15) and was forcibly transported as a slave (37:27-28) much like the victims of transatlantic slavery who were shipped against their will from Africa to the Americas and Europe in the 1400s onwards.

Lessons and Principles

We can rely solely on God for our success at our station abroad

The “world” that 1 Jn 2:15-16 beseeches us not to love (“… all that is in the world—the desire of the flesh, the desire of the eyes, the pride in riches—comes not from the Father but from the world”), Rom 12:2 urges us not to conform to and James 4:4 warns us not to befriend (“Adulterers! Do you not know that friendship with the world is enmity with God? Therefore whoever wishes to be a friend of the world becomes an enemy of God”)—that world would have us believe that the highway to success consists of a single lane along which an eye-catching billboard stands with the following neon message: “ success through all means necessary however unorthodox.” On the other hand, the Bible in general and the story of Joseph in particular, uncovers and points us to an alternate lane

along which an eye-catching billboard stands with the following neon message: “ success through all means necessary however unorthodox.” On the other hand, the Bible in general and the story of Joseph in particular, uncovers and points us to an alternate lane above which is calligraphed the countering dictum “ choose to rely on God instead.”

above which is calligraphed the countering dictum “ choose to rely on God instead.”

In each of the three stations that Joseph finds himself, the Bible records that, yes, he experienced success but more relevantly the success is considered the event with God as the cause. As a domestic worker in Portiphar’s residence, “the Lord was with Joseph, and he became a successful man” (Gen 39:2, cf. vv 3-4). As a convict in the King’s prison “… the Lord was with him; and whatever he did the Lord made it prosper” (39:23). At the top of his game as a civil servant, Joseph testifies as such: “… God… has made me a father to Pharaoh, the lord of all his house and ruler over all the land of Egypt” (Gen 45:8).

Reliance in God is not incompatible with our responsibility to take the necessary and orthodox steps to enhance our success at our station abroad

As much as the Bible attributes Joseph’s success to God, the same Bible paints a picture of a Joseph not passively waiting on God for a job but actively taking two necessary and orthodox steps that enhance anybody’s chances of both getting and staying hired.

One of the steps is networking. The dictionary defines networking as the act of cultivating “people who can be helpful to one professionally, especially in finding employment or moving to a higher position.” It all boils down to developing friendships and establishing rapports with people around you. The conversation that Joseph struck with a downcast baker while the two were confined (Gen 40:7) and the relationship that this rapport must have ushered proved advantageous to Joseph later on when the now reinstated baker sensed the need to return a favor by mentioning Joseph favorably to the King (Gen 41:9).

The other step is providing your potential boss with a cogent reason as to why the company will benefit from your hire. In the case of Joseph his God-given ability to interpret dreams earned him an audience with the King (Gen 41:14) and his astute proposal in light of the forthcoming drought so impressed the King hired him as the CEO of the “famine curbing initiative” (vv 33-44).

Our success abroad should translate into our assisting our families and relatives at home

A report by the World Bank and African Development Bank on remittances to Africa from Diaspora clearly shows that I am really preaching to the choir on the issue of the Diaspora providing assistance to families and relatives at home. African countries received a staggering US $406 billion from remittances from abroad in 2010, the largest net inflow of foreign funds after Foreign Direct Investment. To this end we are most Joseph-like in the sense that Joseph leveraged his influence and success to facilitate the exodus of Jacob (Israel) and his seventy descendants away from famine-ravished Canaan to the bread basket of the world at that time.

The Rest of the Jacob family and the generations following

Circumstances Surrounding their Immigration

With reports of famine in certain parts of the world, it should not surprise us that, as was the case with the Jacob family, food scarcity may be a reason why some of us headed abroad. Personally the decision to leave home was provoked by a paucity of a different sought, viz., scarcity of higher education opportunity due to unavailability of a preferred program (having obtained a Masters in Divinity and desiring to further my education possibly to a doctoral level neither of the two post-graduate schools offering theological degrees in my homeland at that time had in place a doctoral program). Lack of scholarship and imbalance between the number of qualified candidates and the enrollment capacity of the educational institutions are the other reasons why higher education is out of reach for many. A friend of mine was driven abroad by yet another kind of famine—scarcity of jobs. Despite having matriculated from a reputable university with a degree in architecture, he could not find a job

Lessons and Principles

Heads-up, anti-immigration sentiments are as old as Moses

Besides perennial racism, there are at least four moments when societies turn antipathetic towards the immigrant population in their midst: (a) times of  elevated unemployment rate resulting in competition for limited job openings (b) periods of budgetary strains leading to a scramble for social services (c) break out of war or hostility causing a build-up of suspicion of a particular immigrant group due to the existence of ethnic or religious ties between the group and the enemy (d) when the immigrant population approaches or turns majority raising fears of

elevated unemployment rate resulting in competition for limited job openings (b) periods of budgetary strains leading to a scramble for social services (c) break out of war or hostility causing a build-up of suspicion of a particular immigrant group due to the existence of ethnic or religious ties between the group and the enemy (d) when the immigrant population approaches or turns majority raising fears of loss of cultural identity.

loss of cultural identity.

Exponential increase in the population of immigrants and the accompanying possibility of aliens joining forces with the enemy and effectuating their own exodus was the alarming factor some 300 years after the death of Joseph and the rest of the first generation immigrants to Egypt (Exod 1:9). In response Egypt sought to stem the alien population growth by initially subjecting the immigrants to harsh labor (1:11) and when this measure proved counter-productive, the King resorted to infanticide (1:16).

While the killing of the newborn as a measure of curtailing immigrant population is not on the table in America, it is interesting that groups that seek to freeze the number of immigrants who are eligible to vote seek to re-write the 1886 citizen clause of the 14th amendment so as to exclude infants born to a couple who reside illegally in the country.

exclude infants born to a couple who reside illegally in the country.

Keep the faith, Our God is the God of the Exodus

Going with the general definition of a prison as “any place of confinement” Egypt became a  prison the moment her King betrayed his desire to thwart the possible departure of the Hebrew Immigrants (1:10). In the same way that the descendants of Jacob became victims of Egyptian internment, so do many immigrants abroad feel hemmed in their host countries by factors that include lack of airfare, unwillingness to relocate prematurely, and the recognition that their host countries will not reissue permission to come back. Exodus for these would take the form of financial ability to exit at the time of their choosing and the assurance of returning if they so desire.

prison the moment her King betrayed his desire to thwart the possible departure of the Hebrew Immigrants (1:10). In the same way that the descendants of Jacob became victims of Egyptian internment, so do many immigrants abroad feel hemmed in their host countries by factors that include lack of airfare, unwillingness to relocate prematurely, and the recognition that their host countries will not reissue permission to come back. Exodus for these would take the form of financial ability to exit at the time of their choosing and the assurance of returning if they so desire.

The Quartet: Daniel, Hananiah, Mishael, and Azariah

Circumstances Surrounding their Immigration

The manner in which the Quartet arrived abroad compares with Joseph’s involuntary trip to Egypt. The four were part of the inhabitants of Judah forcibly carried away to Babylon after the Lord allowed Jerusalem and her King Jehoiakim to fall into the hands of Nebuchadnezzar. Jehoiakim alias Eliakim succeeded his brother Jehoahaz as King of Judah after the latter was deposed by Pharaoh Neco and taken away to Egypt in 608 BC (2 Kings 23:34). After three years of vassallage, Jehoiakim rebelled against Nebuchadnezzar (2 Kings 24:1). In turn Nebuchadnezzar came to Jerusalem, besieged it, and after it fell, confiscated some of the vessels of the temple and carried off a portion of the population (Dan 1:1-2) (cf. Jer 25:9) (Ezek 23:22-25). Where the trip of the tetrad differs from Joseph’s is the reason. Joseph was sold to slave traders out of hatred. The deportation of Judah was due to the sins of Manasseh (2 kings 24:3; cf 2 kings 21:1-17) and the wickedness of Judah as a whole (Jer 25:5-7; cf Ezek 22: 6-15; 36: 17-19; 39:23).

Lessons and Principles

With God as the wind beneath our wings, upward mobility within our line of work is ours to experience

The foursome started off their career as trainees. Don’t we all? For some its on-the-job training or boot-camp. For others it’s a certification training program . For yet others its an associate or undergraduate degree. The prerequisite for admission to the State-sponsored training included perfect physique, handsomeness, knowledgeableness, a knack for code-cracking Intel, and insightfulness (Dan 1:4). The training itself was to last 3 years. The curriculum included Chaldean Literature and language. Scholarship was available in the form of free boarding, food and wine (Dan 1:5).

As a side note you know you are abroad if your name(s) is (are) subjected to any or all of the following treatments: (a) the nomenclature of the host country overrides yours (since I am “Nicholas Oyugi Odhiambo,” my tribe’s naming system calls for my wife and my kids to pick up only my middle name; yet my student visa reached me by mail with both my middle name and surname attached to her first name; she could just as well be married to my dad now), (b) mis-spelt (I can’t tell you how many time packages has arrived with my name mis-spelt as Odihambo), (c) mispronounced (the “dh” in Odhiambo is supposed to sound as “th” in the word “another” and not a “d” as in the word “door”), (d) shortened either because its too long or too hard to pronounce (so now they call me Mr “O”), or (e) replaced altogether by a local name, thereby camouflaging your original identity. Joseph was on the receiving end of this last treatment. Pharaoh renamed him Zaphenath-paneah. The Quartet were treated likewise. Daniel (“God is judge”) became Belteshazzar (a name associated with a Babylonian god (cf., Dan 4:8), Hananiah (“Yahweh has been gracious”) was renamed Shadrach, Mishael (“who is God”) was now being referred to as Meshach, and Azariah (“Yahweh has helped”) was forced to answer to Abednego. A modern-day example of name change is this gentleman: His childhood friends knew him as Stephen Cherono. Today, thanks to an alleged one million Kenya shillings for switching citizenship and more thanks to efforts by Qatar to arabize and may be even Islamize him, he now goes by the Arabic name Saif (“sword”) Saaeed Shaheen

His childhood friends knew him as Stephen Cherono. Today, thanks to an alleged one million Kenya shillings for switching citizenship and more thanks to efforts by Qatar to arabize and may be even Islamize him, he now goes by the Arabic name Saif (“sword”) Saaeed Shaheen

Upon successful completion of their training, the four amigos were posted at the equivalent of the Office of the President. A year later, in a process only attributable to God, Daniel received his first promotion (Dan 2:48). This is how the God-engendered promotion went down. The Head of State experienced a dream whose meaning he could not unpack. Clueless about the meaning and thus vulnerable to deception by the government-employed code-crackers in the Department of Intelligence, the President tied the credibility of their interpretation to the verifiable challenge of correctly divining the content of his dream. Meeting this challenge served as the basis of Daniel’s promotion. But credit for the ability to meet this particular challenge was given to Deity both by the Babylonian wise-men (v. 11) and by Daniel himself (vv. 19, 28). Four Babylonian Presidents later, Daniel would receive yet another promotion. This time he would be elevated to a position two people away from the presidency– the equivalence of Speaker today (5:29). The basis for the promotion was his ability to decipher the meaning of mene, mene, tekel, parsin (vv 26-28). But even this time this ability is ultimately ascribed to “spirits of the gods” that indwelt Daniel (v. 14).

We should be willing to expose ourselves to harm, even bodily harm, in our determination to remain true to our walk with God

At the same time that Daniel received his first promotion, his three friends were similarly elevated on the strength of Daniel’s recommendation. But unlike Daniel who remained stationed at the King’s Palace (2:49), the trio was sent to the field as administrators. It was while they where out there that the President convoked his whole administration to a dedicatory event whose agenda, as pronounced by the Presidents via the Master of Ceremony, ran counter to the first two commandments. Rather than obey His Excellency and in effect break the commandments, the three, who at this point were being referred to by their given names, made the difficult choice of disobeying the King and by so doing expose themselves to serious harm (3:16-18). A number of decades later, Daniel would be faced with the same twin choices of either compromising his walk with God and escape harm or stay true to his walk with God and suffer harm. He chose the lion’s den instead (Dan 6).

Esther and Mordecai

Circumstances Surrounding their Immigration

Every immigrant can be classified as either second generation and beyond, meaning the person was born abroad or (b) first generation, indicating that the person personally undertook the trip abroad. The term 1.5 generation refers to minors who have made their way abroad usually in the company of an adult parent or relative. Most of the immigrants that have featured in our discussion so far were either first generation (e.g., Abraham, the Jacob family, Daniel and his three friends) or 1.5 generation (e.g., Lot, Joseph, Jacob’s little ones [Gen 46:5]). But we did come across a group that fits the category of second generation and beyond, viz., members of the lineage of Jacob who were born in Egypt. Prominent members of this group include Moses and his two siblings, Aaron and Miriam.

Like Moses in Egypt, Esther and Mordecai in Persia belong to the category of second generation and beyond. Specifically the two were fourth generation. Their respective dads (Abihail and Jair), who would have been third generation, were brothers. It was the grandfather of these two siblings who was first generation having being brought to Babylon as a captive alongside King Jeconiah in 598 BC by King Nebuchadnezzar.

Lessons and Principles

A tip on how to approach a job interview: Don’t ask, don’t tell

A vacancy arose for the position of First Lady to King Ahaseurus (aka Xerxes) following the dismissal of Queen Vashti (Esther 1:19-22). An advert went up. The qualifications were three-fold: young, beautiful, virgin (2:2). Believing that she fitted the bill, Esther answered the Ad most probably under her Persian name, Esther, not her Jewish name, Hadassah. And when it came to the interview itself, she followed her adopter-coach’s tip not to volunteer information about her Jewish background, revelation of which we can only suspect would have been an immediate disqualifier (v 10).

Advocates of Immigrants’ Rights and Welfare, please raise your hands

Look around and note whose hand is raised alongside yours. Moses has his hand up and rightly so. The marching orders he receives from Yahweh could not be any more advocative: “I have observed the misery of my people …; I have heard their cry on account of their taskmasters. Indeed, I know their sufferings, and I have come down to deliver them …, and to bring them up out … So come, I will send you to Pharaoh to bring my people, the Israelites, out of Egypt” (Exod 3:7-8,10). And my-my, did he leave up to expectation! Twelve times he and his brother appeared before Pharoah to demand release from captivity (5:1-4; 7:10-13; 20-23; 8:8-12; 25-30; 9:27-33; 10:3-6; 8-11; 16-18; 24-29; 11:4-8; 12:31-32).

Esther also has her hand raised. Frightened at first to step into the role of an advocate for the assignment sometimes carries with it a price tag that can be too high to pay, she finally did under the goad of her cousin Mordecai. Listen to her plead her case on behalf of her fellow immigrants: “If I have won your favor, O king, and if it pleases the king, let my life be given me—that is my petition—and the lives of my people—that is my request. For we have been sold, I and my people, to be destroyed, to be killed, and to be annihilated. If we had been sold merely as slaves, men and women, I would have held my peace; but no enemy can compensate for this damage to the king.” (Esther 7:3-4)